Programma 17e Saqqara-dag, 15 juni 2019 (in Dutch)

Zaterdag 15 juni 2019

9.00-18.00u

Lipsius-gebouw (Universiteit Leiden)

Cleveringaplaats 1

| 09:00-09.45u | Inschrijving en ontvangst met koffie/thee | |

| 09.45-10.00u | Opening 17e Saqqara-dag door de voorzitter van Friends of Saqqara | Vincent Oeters |

| 10.00-10.45u | The tomb of the army general Iwrkhy and related genealogy problems (Engelstalig) | Ola el-Aguizy (Cairo University) |

| 10.45-11.15u | Pauze met koffie/thee | |

| 11.15-12.00u |

Detective Hormin: verloren graf en verdwaalde objecten

|

Fania Kruijf |

| 12.00-14.00u | Lunchpauze (op eigen gelegenheid) | |

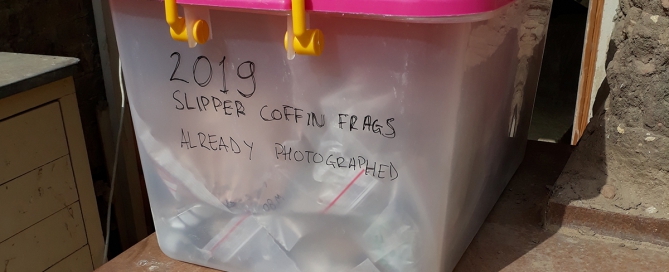

| 14.00-14.20u | Saqqara Newsflash: bijzondere ontdekkingen in het nieuws | Carolien van Zoest |

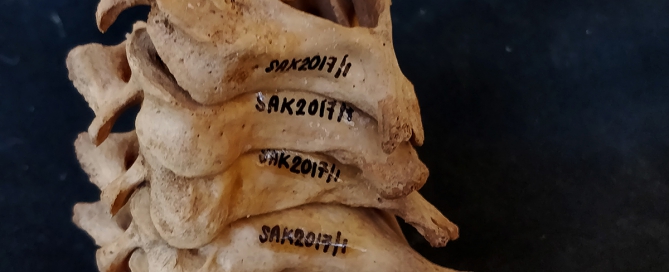

| 14.20-14.40u |

Fysische antropologie: botten laten spreken

|

Ali Jelene Scheers |

| 14.40-15.15u | Pauze met koffie/thee | |

| 15.15-16.15u | Verslag van het opgravingsseizoen 2019 in Saqqara door de opgravingsleiders | Lara Weiss |

| 16.15-16.30u | Loterijtrekking | |

| 16.30-18.00u | Afsluitende borrel | |

| vanaf 18.00u | Diner in restaurant Verboden Toegang (optioneel) |

Donateurs gratis, studenten € 5, anderen € 10 entree (incl. koffie en thee, excl. lunch en diner).

Deelname aan het aansluitende diner in restaurant Verboden Toegang kost ca. € 25 à € 30 (à la carte).

Verdiep uw kennis van het oude Egypte, leer meer over de begraafplaats Saqqara, ontmoet de wetenschappers die er werkzaam zijn èn uw mede-geïnteresseerden, sla uw slag op de tweedehands boekenmarkt, doe mee met een spannende loterij en geniet samen met ons van een afsluitend diner. Mis het niet!