Digging Diary 6, 20-24 April 2019: See you next year, insha’allah, Saqqara!

Time flies when you’re having fun! We find ourselves at the end of the season and have closed the site and securely placed all finds in the storerooms. These include many fragments of “slipper coffins” and linen textile. Some interesting finds were made this week in the new tomb north of Maya, which is now better understood, and which we will continue to excavate next year. We are thankful to all team members and workmen for a very successful season, and to you for reading our Digging Diaries!

A box full of slipper coffin fragments excavated this season. Photo: Daniel Soliman.

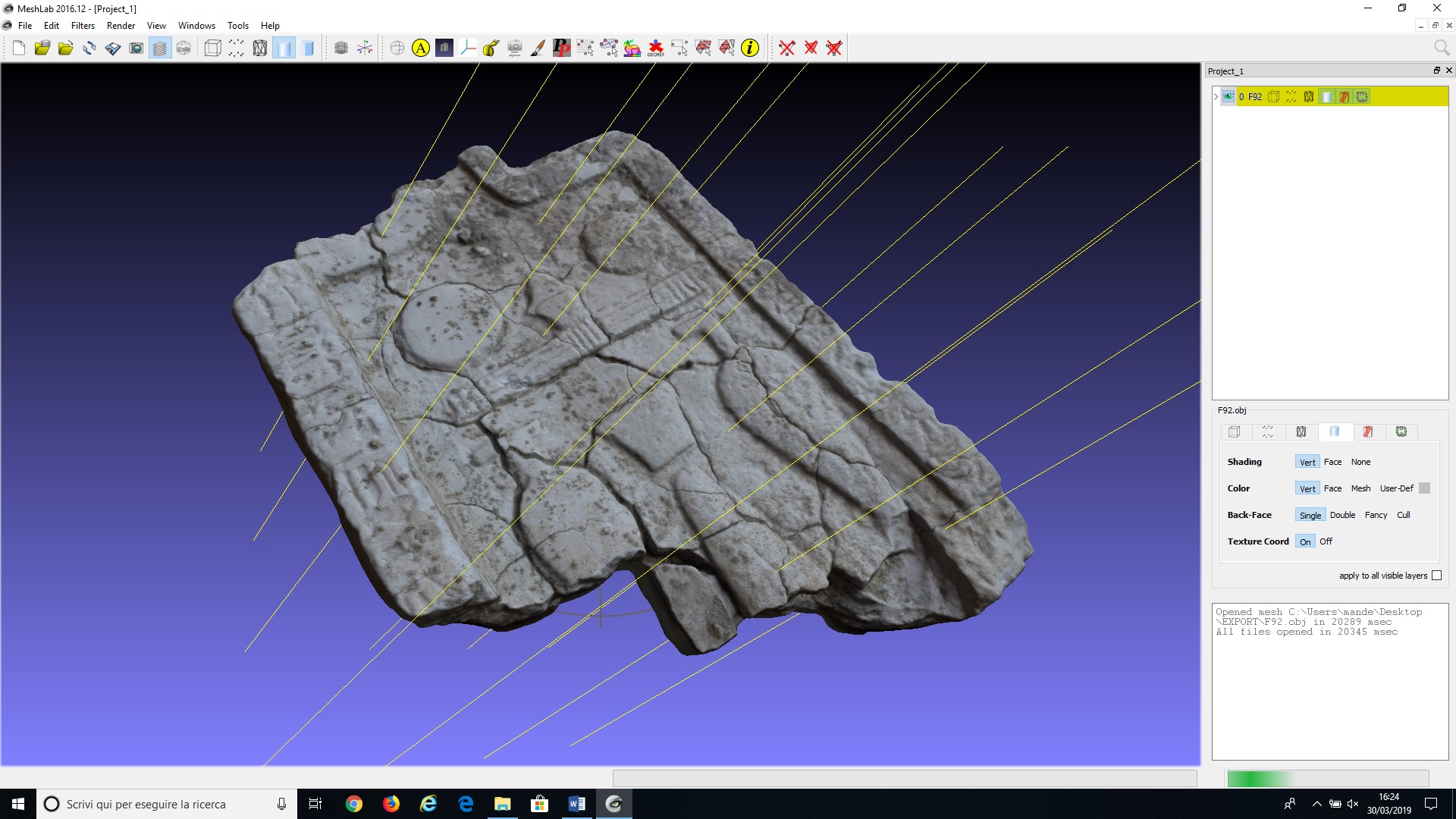

Time flies when you’re having fun, and here we find ourselves at the end of the excavation season! Our last day of work was on Tuesday, while we spent Wednesday closing the site and ensuring that all objects are securely placed in the storerooms. All in all it was a shorter, but still rather hectic week. As usual, at the end of the season we wrap up everything, clean all of the excavation area for the final general photos and survey, process the last pottery and bone fragments, and document the last finds. In addition, and very importantly, we had to remove the huge dump of excavated sand we produced during these six weeks of work, to clear the area for future excavations. We also backfilled all the structures we unearthed in order to preserve everything in the best possible way for seasons to come.

The workmen are backfilling the newly excavated tomb to the north of Maya to preserve it for next season. Photo: Daniel Soliman.

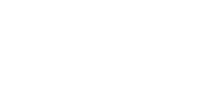

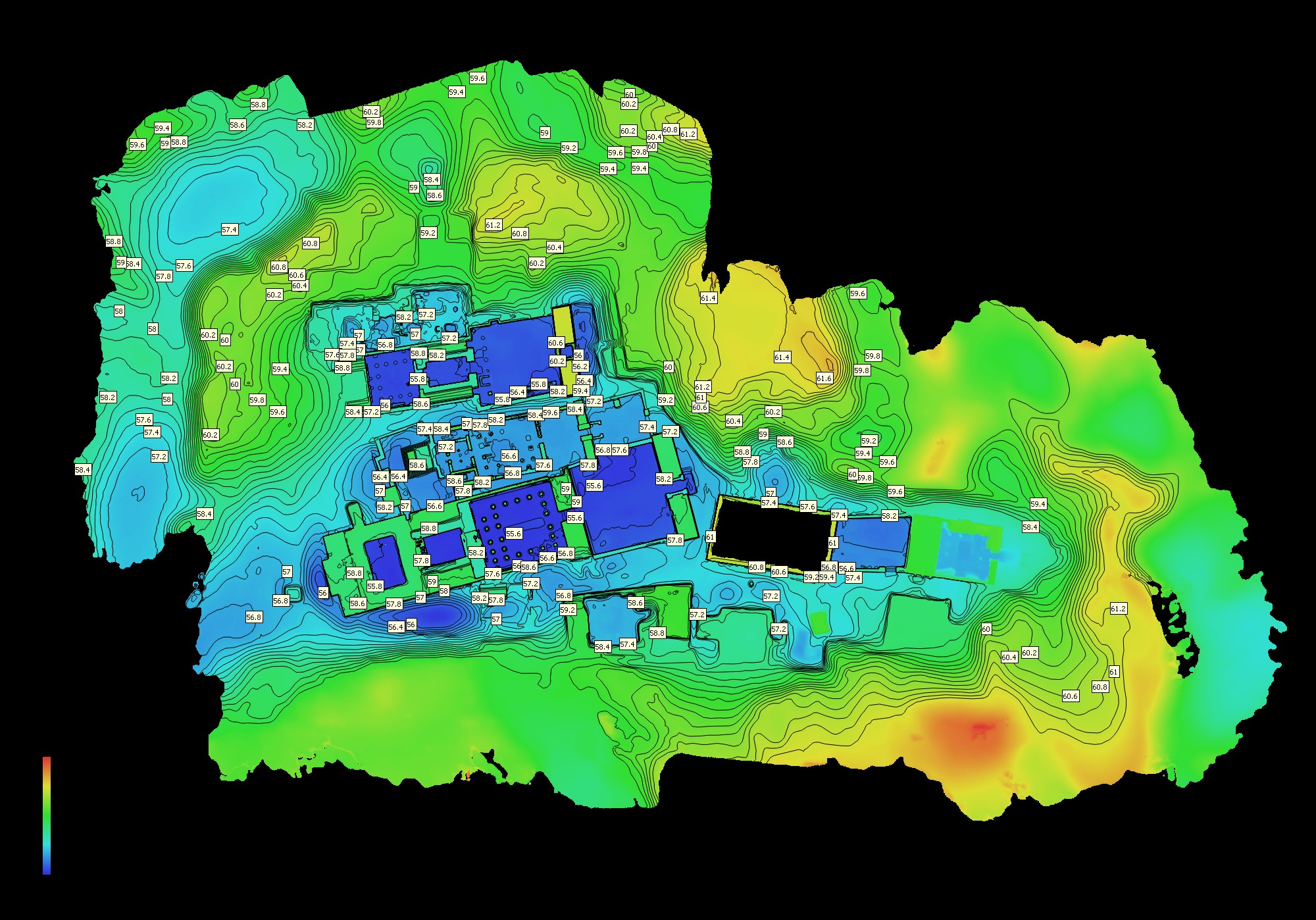

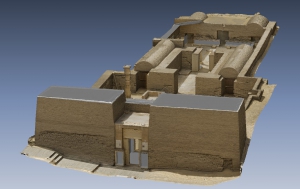

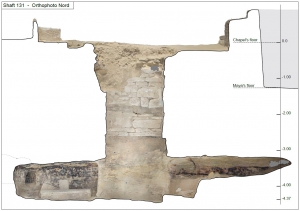

Before doing that, however, we had three more days to continue with the excavation, and we didn’t want to waste a single minute. Therefore, Paolo decided to split our team of workmen in two groups. This allowed us to work simultaneously on the still rather high mound of debris overlooking the structures discovered in the past two years, as well as inside the large tomb found last year and further explored in the present season. We now know the total extension of the tomb and can tell that unfortunately it was heavily plundered, most likely in the 19thcentury. We found the remains of three columns of the central courtyard, and we could determine that the floor of the main entrance is neatly paved with nice limestone slabs. We managed to better understand the relationship of this tomb with the surrounding area, but the excavation of its main funerary shaft and the exploration of its underground chambers must wait till next year. See you in a year, then, very interesting tomb!

A basket full of skeletal remains discovered during the excavations. Photo: Daniel Soliman.

We now know the total extension of the tomb and can tell that unfortunately it was heavily plundered, most likely in the 19thcentury. We found the remains of three columns of the central courtyard, and we could determine that the floor of the main entrance is neatly paved with nice limestone slabs. The excavation of its main funerary shaft and the exploration of its underground chambers must wait till next year.

You might not expect it from the excavation of a dump, but the work brought to light various objects that demanded all of our attention. We found copious amounts of fragments from wood coffins, some with their original paint preserved. But the sands also revealed other material that was used for burials. There were many fragments of linen textile that may have accompanied buried individuals from the Late Antique period. Egyptian linen is famous for its extraordinary quality, and we experienced this first hand as many fragments from shawls, hats and tunics were large and well preserved. This experience serves us very well, because the curators of the National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden are preparing an exhibition on Egyptian textiles that will be opened in 2020.

Reorganised skeletal remains now stored in the subterranean rooms in the tomb of Horemheb. Photo: Daniel Soliman.

One category of objects that has occupied us this season fragments of a type of coffin that Egyptologists funnily enough call “slipper coffins”. These are anthropoid ceramic coffins, usually of Nile silt, that completely enveloped the mummified body. The fragments that we discovered date to the Late Period and are often rather crudely modelled. On occasion, however, we documented fragments with nice decoration and traces of paint.

Meanwhile, on the site, we are regaled by the stories of our Egyptian team members. The older ones among them have been working at Saqqara excavations for many years, and they remember the many discoveries made. During an idle moment while reorganising our storerooms in the subterranean chambers of the tomb of Meryneith, Assam Azmi told us about the famous moment when he discovered the statue of Meryneith together with Maarten Raven and René van Walsem. The statue has since found a new home in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

Daniel and Nicola leave the site. Photo: Ali Jelene Scheers.

The team has now packed up and said their goodbyes to our wonderful staff who took good care of us at the dig house. After a long day’s work in the sun, we used to come home to Atef, Mahmoud and Fahim who welcomed us with a cold glass of home-made lemonade. Together with them we have celebrated the birthdays of some of the team members, and we were happy to return the favour by cooking gnocchi for Atef’s birthday. The team members, tired but content with the work, are now on their way home, where the results of this season will be processed further. We look forward to telling you more soon, first at this year’s Saqqara Day on 15 June 2019!

Paolo Del Vesco, Daniel Soliman, and Lara Weiss

The Saqqara Team says thank you! Photo: Nicola Dell’Aquila.