General information on Ptahemwia’s tomb

Ptahemwia performed the high court function of ‘Royal Butler, Clean of Hands’ during the reigns of the pharaohs Akhenaten and Tutankhamun (1353-1323 BC). In that capacity, Ptahemwia was not only responsible for serving the pharaoh food and drink but also for the supply to the court of all kinds of other commodities. His tomb is located directly to the east of that of Meryneith. Its exact position had hitherto been unknown, although the existence of the complex could be derived from two loose finds: an inscribed limestone pilaster in the Museo Civico Archeologico of Bologna (KS 1891) and an inscribed jamb fragment in the Cairo Museum (JE 8383).

Ptahemwia performed the high court function of ‘Royal Butler, Clean of Hands’ during the reigns of the pharaohs Akhenaten and Tutankhamun (1353-1323 BC). In that capacity, Ptahemwia was not only responsible for serving the pharaoh food and drink but also for the supply to the court of all kinds of other commodities. His tomb is located directly to the east of that of Meryneith. Its exact position had hitherto been unknown, although the existence of the complex could be derived from two loose finds: an inscribed limestone pilaster in the Museo Civico Archeologico of Bologna (KS 1891) and an inscribed jamb fragment in the Cairo Museum (JE 8383).

The tomb was obviously never finished, and it is still unclear whether Ptahemwia died prematurely or fell out of grace. His name, ‘the god Ptah sits in his barque’, may have had a negative effect on his career. Ptah was the city god of the Egyptian capital Memphis, and, like the other gods, was pushed aside by Akhenaten. Ptahemwia’s tomb was plundered in antiquity and later revisited by art robbers in the 19th century. It was rediscovered and fully excavated in 2007 and 2008.

Superstructure of Ptahemwia’s tomb

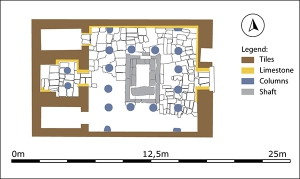

The tomb of Ptahemwia has a length of 16 m and is 10.5 m wide.

It was built in mudbrick and has preserved a considerable part of its limestone paving, wall revetment, and architectural elements. Most walls still stand to a height of approximately 2 m. The eastern entrance wall has a

battered face and may once have been shaped as a temple pylon. It is followed by an inner courtyard with a peristyle of twelve papyriform columns and a shaft to the underground burial chambers. The courtyard is followed by

three offering chapels. The central chapel is preceded by an antechapel with two papyriform columns that once supported a roof with a small mudbrick pyramid on top. It has a limestone floor and limestone wall revetment, whereas the side-chapels just have mud floors and mud-plastered walls.

Substructure of Ptahemwia’s tomb

The main shaft of the tomb is located in the centre of the courtyard. Only one of its covering slabs was found to be extant; this and the presence of drystone walls erected around its aperture betrayed it had already been entered before. The shaft proved to be 9 metres deep. It gives access to an antechamber in the south, leading to a descending corridor and burial-chamber in the west. Presumably, this west complex was originally closed off by limestone slabs laid across the stairwell halfway the corridor, with blocking stones erected on top of them. It should be noted that the west chamber lies almost exactly under the central chapel of the superstructure. A second complex, likewise once blocked by slabs of limestone, opens to the south of the antechamber. This consists of an L-shaped room, leading to a side-chamber with a 4.80 m deep pit and a further burial-chamber at the bottom. The whole underground complex was found largely filled by wind-blown sand, which had penetrated via the main shaft but also via a secondary shaft to the south of the tomb. The latter breaks through the ceiling of the L-shaped chamber. Originally it belonged to an Old Kingdom mud-brick mastaba.

The west complex was found almost empty, doubtless the result of 19th century tomb robbers. On the other hand, the deepest chamber was the only uncontaminated New Kingdom context and still contained a quantity of pottery and some decayed wood of the original coffins deposited here. Otherwise some inlays of coffins (eyes and eyebrows), a few beads, and a scarab with the name of Thutmosis IV were the only finds to attest that indeed the underground complex was used for New Kingdom interments. Unfortunately, inscribed material proving that this concerned Ptahemwia and his relatives was lacking.

Most interesting finds from Ptahemwia’s tomb

Old Kingdom statue

This lower part of a red granite statue was found in clean sand outside the courtyard of Ptahemwia’s tomb. It depicts a man seated on a block-shaped seat without backrest. He is clothed in a short half-goffered kilt, the ‘gala kilt’ of high officials of the Old Kingdom. To either side of the legs is an inscription on the front of the seat, specifying that the person represented had the rank of vizier. Unfortunately, the name is broken off with the front of the statue’s plinth and its feet. However, the fragment can be closely dated to the Fifth Dynasty (2465-2323 BC) and the only contemporary vizier with a tomb close to the New Kingdom necropolis was Minnofer. A sarcophagus of this vizier is now in the Leiden Museum.

Coffin fragment

This fragment of the lid of a painted wooden coffin represents part of a lower arm. It still shows the radiating pattern and curved lines of a collar in black outlines, blue bands and white squares. The coffin from which this fragment came must have represented the deceased in the dress of daily life. Similar luxurious coffins were a fixed attribute of wealthy Ramesside burials. This indicates that there must have been burials of that period inside the west chapels of Ptahemwia’s tomb, where this fragment was found.

Faience shabti

This mummiform faience shabti was found in the fill of Ptahemwia’s south chapel. Presumably it had just fallen in from the surface of the desert after the roof of the chapel had already collapsed. It is gazed inbright greenish blue with details in black. The front shows four concentric framed lines of hieroglyphs, with ablank column on back. The text mentions the owner of the shabti, the scribe of the granary of the palace (life, prosperity, health!), Amenemone. This official may have had a burial in the immediate vicinity of the tomb of Ptahemwia.

Scarab of Tuthmosis IV

This small scarab of white glazed steatite was the only inscribed object (apart from some decayed planks of a coffin) found in the lower chamber of Ptahemwia’s subterranean complex. Its perforation is still filled with the remains of a corroded bronze ring. Such scarabs were worn on the finger and could be swivelled along a metal axis, so that they could also be used to stamp documents or clay sealings. The undersurface of this seal is inscribed with the throne name of pharaoh Tuthmosis IV (1402-1391 BC): Menkheperure, beloved of Amun. This indicates that the scarab must have been an heirloom, since the rest of the tomb dates to half a century later.

Ptahemwia’s family relations

Objects from Ptahemwia’s tomb in museum collections

Bologna, Museo Civico Archeologico KS1891: pilaster

Cairo, Egyptian Museum JE 8383: door-jamb

Restoration

In 2008, all of the perimeter mudbrick walls of the tomb were consolidated to a minimal consistent height, including the entrance pylon. The chapels on the western side of the courtyard were roofed with a simple timber structure laid to fall, boarded and then waterproofed with bitumen. A layer of mudbricks and mud plaster was placed over this roof to blend with its surroundings. The new roof was required not only to protect the central chapel with its surviving limestone architectural features, but also to provide storage space in the side chapels to accommodate future finds. These chapels were given timber doors, while a steel mesh door was installed in front of the central chapel. Since the tomb’s excavation in early 2007, a temporary timber shelter had been placed over the most precious reliefs on the north and east sides of the courtyard. In 2008, this covering was replaced with a more durable steel-framed shelter, with pull-up louvred shutters that allow viewing of the reliefs at a safe distance, and also provide shade from the full force of the south sun. The roof of the shelter rests on the reconstructed north and east walls of the courtyard, and is fully ventilated. Two separate opening timber cupboards protect the reliefs on the inner door jambs of the entrance.

A small percentage of the limestone lining wall of the tomb’s interior, not covered by the new shelter, was reinstated with new limestone ashlar masonry in order to protect existing relief blocks and provide a visual continuity of this surface in at least the northern half of the tomb. Small areas of missing flooring were also replaced, notably inside the central chapel and immediately outside it where a loose surviving column base was reinstated. A large number of the badly-damaged limestone blocks lining the edge of the burial shaft were replaced with new blocks to define its limits and to provide an abutment for the courtyard paving. The shaft itself was covered with removable reinforced precast concrete planks. At the entrance to the tomb itself, two large monolithic limestone blocks, carved with a batter in profile, were installed as replacements for the lost door jambs. Their dimensions followed the original mason’s marks on the surviving floor slabs. In order to preserve the evidence of the original door pivot and yet keep the new timber entrance door in the same position as its ancient counterpart, the door was raised on a stainless steel bracket at its base. The top of the door was made to pivot from a cantilevered timber beam that was part of a series of beams that formed a continuous lintel over a late-period shaft that had been cut through the face of the north wing of the entrance pylon. A visitor information panel was mounted under this lintel in the void created by the intrusive shaft.

In 2009, five relief blocks were reinstated in their original positions inside the central chapel of the tomb, with two new slabs of limestone reconstructing the lost transverse screen-walls. A further relief fragment was put back on the north wall of the peristyle courtyard.

Bibliography

M.J. Raven, The tomb of Ptahemwia: Akhenaten’s ‘royal butler, clean of hands’, Minerva 18.5 (2007), 11-13.

M.J. Raven, R. van Walsem et al., Preliminary Report on the Leiden Excavations at Saqqara, Season 2007: the tomb of Ptahemwia, JEOL 40 (2007), 19-39.

M.J. Raven, Een nieuw graf in Sakkara: Ptahemwia, dienaar van farao Achnaton, Archeologie Magazine 02/2008, 6-10.

M.J. Raven, H.M. Hays et al., Preliminary report on the Leiden Excavations at Saqqara, Season 2008: the tomb of Ptahemwia, JEOL 41 (2009), 5-30.

M.J. Raven, A new statue of an Old Kingdom vizier from Saqqara, in: A. Woods/A. McFarlane/S. Binder (red.), Egyptian culture and society, Studies in honour of Naguib Kanawati (= Suppl. ASAE 38, Cairo 2010),

119-127.