General information on Tia’s tomb

Tia was Overseer of the Treasury under King Ramesses II (1290-1224 BC). He must have started his career under Ramesses’ father, Seti I, who seems to be mentioned in the tomb. Tia seems to have died around year 31 of Ramesses’ reign, when the tomb was not yet quite finished. Certain parts were obviously executed in great haste or were left undecorated. Tia’s relationship to the pharaoh was very close: he had married the King’s sister, who was also called Tia like her husband. The Saqqara monument was built according to the King’s instructions. It bears the royal cartouches in several places and served as a mortuary temple to the god Osiris. The position of the tomb is significant: it was constructed on the north side alongside Horemheb’s monument, because the latter was regarded as the founding father of the ruling Dynasty. A cult for the general-who-became-pharaoh was installed in Horemheb’s tomb, and a Ramesside princess was buried in one of its subsidiary shafts. Tia’s tomb was excavated from 1982 to 1984 but its forecourt was only uncovered during the seasons 2005-2007.

Overview of the Tomb of Tia

Superstructure of Tia & Tia’s tomb

The tomb’s superstructure measures 45.30 m from east to west and 11,75 m across. It consists of an eastern gateway leading to a forecourt, a flimsy pylon preceded by a portico, an outer courtyard separated by a screen wall from a peristyle inner courtyard, three offering chapels (the central one with a two-columned antechapel), and finally a 6.35 m high pyramid. An exterior stairway led to a roof terrace facing the pyramid. All masonry (except for the mudbrick forecourt) is constructed in limestone. The walls consist of inner and outer orthostats, bonded by an internal core of gypsum mortar and limestone chippings. The inner wall-faces have limestone reliefs of rather bad quality. Many bad patches were repaired in gypsum, with the positive result that a lot of original colour has survived. Representations comprise portraits of the King (pylon) and offering scenes including husband and wife (courtyards and chapels). The south chapel was devoted to the cult of the Apis bull and shows a boating scene and a cortège of nine gods.

Map of the Tomb of Tia

Substructure of Tia & Tia’s tomb

The main shaft opens in the inner courtyard and gives access to an antechamber, followed by a ramp leading to three further chambers. The maximum depth of this complex is 13 m. The main burial-chamber had a large sarcophagus-pit in the floor; additional pits for burials were constructed later. Foremost among the finds from this complex are fragments of Tia’s black granite sarcophagus (another fragment is in the Ny Carlsberg Glyptothek in Copenhagen) and shabtis of husband and wife. Obviously, this complex had been heavily plundered by tomb robbers. Part of their spoils were retrieved in 2004, in a heap on the forecourt of the adjacent tomb of Horemheb. This robbers’ dump proved to contain additional elements of Tia’s sarcophagus, shabtis and canopic jars of both husband and wife, skeletal material, and the coffin and bones of several pet monkeys. Two subsidiary shafts, once topped with small chapels of their own, were cut in the outer courtyard for two of Tia’s retainers. The southern shaft, belonging to Tia’s secretary Iurudef, could be excavated in 1985; the northern one is too unstable to be entered. Two similar shafts were excavated on the forecourt in 2007, but these did not provide any inscribed material. Both of these shafts were associated with a free-standing stela, of which the northern one partly survives.

Most interesting finds from Tia & Tia’s tomb

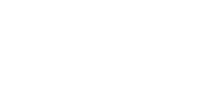

Hieratic docket

Hieratic docket

Fifteen large pottery amphoras were found in the area between the staircase of the tomb of Tia and the north wall of Horemheb’s tomb. It is unknown whether these belonged with Tia’s burial or rather with the Ramesside interments in a shaft on Horemheb’s first courtyard. The type of amphora dates certainly to Dynasty XIX. Two of these amphoras bore hieratic dockets in black ink, stating that they contained ‘water of the flood brought from Patjuf’ and ‘water of the Xoite nome brought from the Xoite nome, from the western river’. These inscriptions indicate that inundation water brought from specific areas in the Delta played some part in the offering-rituals in New Kingdom tombs, presumably because it was attributed with special revivifying effects. Similar water jars have been found in the adjacent tomb of Maya.

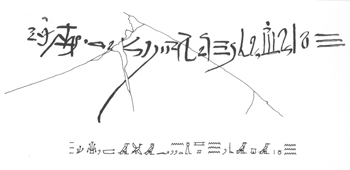

Sarcophagus fragments

Sarcophagus fragments

The granodiorite sarcophagus of Tia is known to us from a total of twenty-five fragments. Most of these were found in a dump left by tomb robbers on the forecourt of the tomb of Horemheb, Tia’s neighbour in the cemetery. Several other fragments were found dispersed over the superstructure of Tia’s own tomb, the nearby tomb of Pay, or inside Tia’s burial-chambers. One part has been in the Ny Carlsberg Glyptothek in Copenhagen since the 1890s. Quite a lot of the sarcophagus is still missing. Obviously this once beautiful object was smashed by robbers who were hoping to find treasures on the mummy of the tomb-owner. The sarcophagus depicted Tia as a mummy with striated wig and ornamental collar. Long columns of incised hieroglyphs ran over the full length and width of the lid and down the sides. These bands framed compartments occupied by representations of the usual funerary deities protecting the deceased.

Pet-monkey coffin

Pet-monkey coffin

An unexpected find in the robbers’ dump on the forecourt of the tomb of Horemheb consisted of this lid of a wooden sarcophagus for a monkey. Although monkeys are often represented as pets, actual finds of their remains are not common at all. The Tia dump contained skeletal parts of at least nine monkeys: two of these are baboons, two others have been identified as a green monkey and possibly a Diana monkey, and the others are immature and cannot be identified with any certainty. These monkeys were imported from Central Africa to serve as pets. Their bones show traces of disease and malnutrition. Tia seems to have been a man of unusual tastes, and the care with which he interred his favourite pets in his own tomb is an example of that. Earlier excavations in his tomb have uncovered the remains of a cat in a wooden box.

Canopic coffinettes

Canopic coffinettes

A robbers’ dump on the forecourt of the tomb of Horemheb contained a great number of broken objects inscribed for Tia, the overseer of the treasury who was buried next to him. Among the finest objects from the dump were the parts of two containers in the shape of a mummy or coffin. These are made from a single piece of semi-translucent alabaster, with expressive facial features and transverse and longitudinal bands of inscription. Such ‘coffinettes’ are a rare alternative for the more common vase-shaped canopic jars used to preserve the embalmed intestines of the deceased. Such jars come in sets of four and have stoppers shaped like human or animal heads. It is rather problematical, therefore, that the same dump comprised parts of at least three alabaster canopic jars of Tia. If he already had a set of four jars, what purpose did the coffinettes serve in his burial outfit?

Tia’s Family Relations

Objects from Tia & Tia’s tomb in museum collections

- Durham, Oriental Museum N. 1965: stela (original position unknown)

- Copenhagen, Ny Carlsberg Glyptothek AE IN 48: fragment of Tia’s sarcophagus

- Florence, Museo Archeologico 2532: stela (from north wall of inner courtyard)

- Leiden, Rijksmuseum van Oudheden F 1987/3.10-11, .13-15: two shabtis of princess Tia, stela fragment, mask of coffin, basket (excavated finds received as part of partition)

Bibliography

Final report:

Martin, G.T., et al., The Tomb of Tia and Tia, a Royal Monument of the Ramesside Period in the Memphite Necropolis (London, 1997).

Additional Notes:

Raven, M.J., V. Verschoor, M. Vugts and R. van Walsem, The Memphite Tomb of Horemheb, Commander-in-Chief of Tutankhamun, V: The Forecourt and the Area South of the Tomb, with Some Notes on the Tomb of Tia (Turnhout, 2011).

Restoration

Unlike all of the other larger tombs in the necropolis, the monument of Tia was constructed almost entirely out of limestone. This meant that it had served as a useful quarry over the centuries. Little of the original structure remained apparent after excavation. The tomb also had a separate small pyramid at its rear, clad with limestone over a rough mudbrick and rubble core. Following excavation in the early 1980s, a limited restoration took place. This included the partial reconstruction of a number of square pillars in plastered brick; the building up of stone rubble

walls around the south chapel with its surviving relief decoration; and the reinstatement of some of the pyramid’s facing blocks.

In 2006, a second phase of work was commenced. This included the rebuilding of the perimeter wall of the tomb in stone rubble with lime mortar. Clues for their outlines were given by surviving stonework and builders’ marks on paving slabs. All the rubble walls were then plastered with a lime render to create a clear distinction between original and new work. A number of decorated blocks from the tomb were put on display in a series of covered niches set over the reconstructed walls. The entire area of the tomb chapels was roofed with a new steel frame structure in order to protect the original reliefs. The decayed core of the pyramid was consolidated with limestone rubble in a stepped section, later rendered. The stone pylon at the entrance to the tomb was consolidated in a similar manner, and a new visitor information panel was mounted here. Opening ventilated timber cupboards were also installed here in four exposed locations. The mudbrick walls of the forecourt were restored and gaps in the pavement filled with new stone.